Gabbro is a coarse-grained (phaneritic), mafic intrusive igneous rock. It forms when iron- and magnesium-rich magma cools slowly beneath the surface. Gabbro is the intrusive equivalent of basalt, meaning both have similar chemistry but different cooling histories.

It makes up a large proportion of the lower oceanic crust, especially at mid-ocean ridge magma chambers. It also occurs in large, layered intrusions on continents. Gabbro frequently contains calcium-rich plagioclase and clinopyroxene, which give it its characteristic dark color and high density.

Gabbro is a key rock for studying crustal growth, mantle melting, and magmatic differentiation. It is also economically important because it can host Ni-Cu-PGE sulfide ore systems.

Classification and tectonic settings

- Rock type: Plutonic, mafic, intrusive igneous rock

- Origin: Slow cooling of mafic magma in the crust

- Magma series: Tholeiitic or alkaline depending on setting

- Silica content: Low; 45%–52%

- Primary minerals: Plagioclase (labradorite → anorthite), clinopyroxene (augite)

- Tectonic settings: Divergent plate boundaries (mid-ocean ridges), Continental rifts, Layered intrusions in stable cratons, Ophiolite complexes (obducted oceanic crust)

Physical and mechanical properties

- Color: Dark gray, green-black, or black

- Grain size: 1–10 mm, can be >20 mm in pegmatitic zones

- Mohs hardness: 6–7

- Density: 2.7–3.3 g/cm³

- Magnetic behavior: Often weak to moderate magnetism from Fe-Ti oxides

- Durability: Very high resistance to chemical weathering and abrasion

- Compressive strength: Commonly >200 MPa

- Porosity: Very low due to interlocking crystals

- Permeability: Very low in fresh samples

How to identify gabbro in the field

Gabbro is identified by dark color, coarse crystalline texture, high weight, and absence of quartz. Quartz is almost never visible in fresh gabbro, making it easy to distinguish from felsic intrusive rocks.

Fresh surfaces often show pyroxene cleavage at ~90° and plagioclase striations from polysynthetic twinning. Weathered gabbro may turn greenish but still retains coarse grains and high density.

Gabbro lacks glassy or conchoidal fracture because it crystallizes fully at depth. The rock breaks along mineral cleavage rather than forming curved shell-like fractures.

A hand sample of gabbro will feel noticeably denser and heavier than granite, diorite, or rhyolite. This is a reliable first field clue. More ways are:

1. Colors of gabbro

Gabbro is most often dark gray to black, controlled by the high amount of mafic silicates and calcium-rich plagioclase. The typical color is not black uniform. Instead, it appears speckled or mottled because light plagioclase crystals contrast with dark pyroxene.

A green-black or olive-green color occurs in varieties containing olivine or altered pyroxene. This is less common than dark gray. It often signals formation from more primitive or Mg-rich magma.

A dull green or chlorite-rich green can appear when the rock undergoes hydrothermal alteration. Fluids convert pyroxene into amphibole, chlorite, or episode. This is most typical in ocean-floor gabbro from ophiolite complexes.

Rare color variants include very dark green, almost black-green when pyroxene content is extremely high. Some gabbros may develop rust-brown staining on exposed surfaces when iron oxides weather. This is a surface effect, not a fresh rock color.

Gabbro almost never contains pink or white tones. These colors are typical of alkali feldspar-rich rocks. Gabbro contains <10% alkali feldspar. So those colors are absent in fresh samples.

2. Textures of gabbro

- Phaneritic (coarse-grained): The most typical texture. Pyroxene and plagioclase crystals are visible and similar in size. Forms from slow cooling in plutons.

- Ophitic texture: Plagioclase laths are enclosed inside larger augite crystals. Augite forms the enclosing mineral. Plagioclase crystallized earlier.

- Sub-ophitic texture: Partial enclosure of plagioclase in augite. The enclosing augite crystals are smaller than in fully ophitic samples.

- Cumulus texture (cumulate gabbro): Early-formed crystals settle by gravity. Cumulus minerals are plagioclase, pyroxene, or olivine. Intercumulus minerals crystallized later.

- Layered texture (rhythmic modal layering): Alternating mafic and plagioclase-rich bands. Common in layered intrusions. Formed by fractional crystallization and crystal settling.

- Porphyritic texture (rare but present): Phenocrysts: pyroxene or olivine. Groundmass: finer plagioclase + pyroxene. Forms when cooling rate changes.

- Poikilitic texture: Large oikocrysts of pyroxene or amphibole enclose many smaller plagioclase or olivine grains. Indicates extended crystallization.

- Pegmatitic gabbro: Very coarse crystals (>20 mm). Common minerals: pyroxene or plagioclase megacrysts. Formed in late-stage melts rich in volatiles.

- Cataclastic or deformed gabbro:

Grains show fracturing and foliation-like alignment. Caused by tectonic stress in shear zones or during obduction in ophiolites.

3. Other physical Identification clues

Gabbro shows pyroxene cleavage at near-right angles (~90°). This is one of the most diagnostic features on broken surfaces.

Plagioclase crystals often show parallel striations or twin lamellae. This reflects polysynthetic twinning. It is visible even in hand sample.

The rock is very heavy for its size. This is due to Mg-Fe-Ca enrichment. This physical clue is often the fastest field check.

Gabbro often has a greasy to metallic luster on fresh broken surfaces. This occurs when magnetite or ilmenite are present.

The rock does not show glassy fracture or curved breaks. Quartz is very low (<5%). So conchoidal fracture is absent.

Chemical composition of gabbro

Gabbro is a mafic and basic rock. It is enriched in heavier elements (Mg, Fe, Ca) and depleted in light elements (Si, Na, K).

Typical geochemical composition varies slightly by magma type and location. A representative whole-rock composition is:

SiO₂: 46%–52% — reflects basic silica range, TiO₂: 0.8%–2.5% — controlled by Fe-Ti oxide crystallization, Al₂O₃: 13%–18% — supplied by plagioclase formation, Fe₂O₃ + FeO: 8%–14% total Fe — indicates strong mafic signature, MnO: 0.1%–0.3% — trace mafic component, MgO: 6%–12% — influenced by olivine and pyroxene, CaO: 8%–13% — reflects calcic plagioclase, Na₂O: 1.5%–3% — minor feldspar component, K₂O: 0.1%–1% — low total alkalis, P₂O₅: 0.05%–0.4% — hosted by apatite.

Mineral composition of gabbro

1. Primary Minerals

Gabbro’s crystal framework is formed mainly by calcic plagioclase feldspar. The anorthite amount is commonly >50%. This means compositions range from labradorite to bytownite and sometimes anorthite. Plagioclase occurs as subhedral to euhedral tabular laths, often showing visible striations from twinning.

Clinopyroxene (usually augite) crystallizes after plagioclase in most gabbros. It fills the spaces between feldspar grains or forms larger enclosing crystals in ophitic textures. Pyroxene grains show two-directional cleavage at right angles (~90°), a critical identification clue.

Olivine appears in more primitive gabbros. It forms rounded, high-relief grains without cleavage. Olivine amount can reach 5%–25% in olivine gabbro.

2. Accessory minerals

Gabbro commonly contains magnetite and ilmenite, which form opaque, black, metallic grains scattered through the rock. These minerals increase density and produce weak to moderate magnetic response.

Apatite occurs as tiny acicular or prismatic crystals. It holds most of the rock’s phosphorus. Zircon and baddeleyite can appear in trace amounts in evolved gabbro.

Hornblende may form if the magma contained sufficient water. It replaces pyroxene during late-stage crystallization or alteration. This produces greenish weathered surfaces.

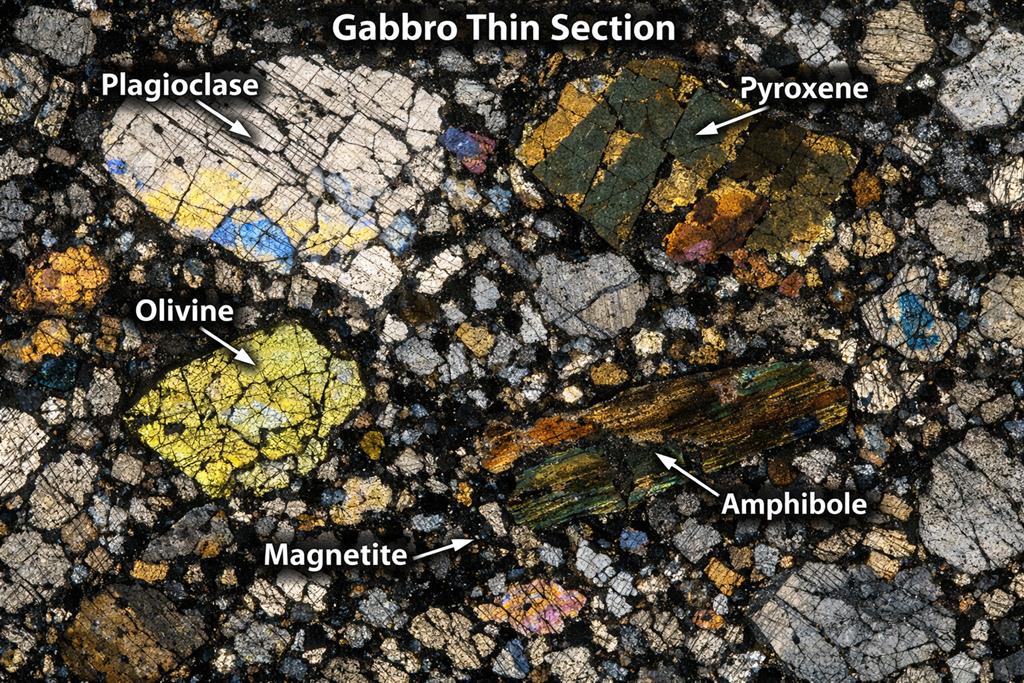

3. Gabbro in thin section

In thin section, plagioclase shows albite and pericline polysynthetic twinning. The twin lamellae are sharp and continuous.

Augite exhibits high relief under plane-polarized light. It commonly shows second-order interference colors under cross-polarized light.

Olivine shows bright birefringence and no cleavage. It may exhibit iddingsite rims if altered.

Opaque oxides appear as black grains. They do not transmit light. This is diagnostic for Fe-Ti oxide presence.

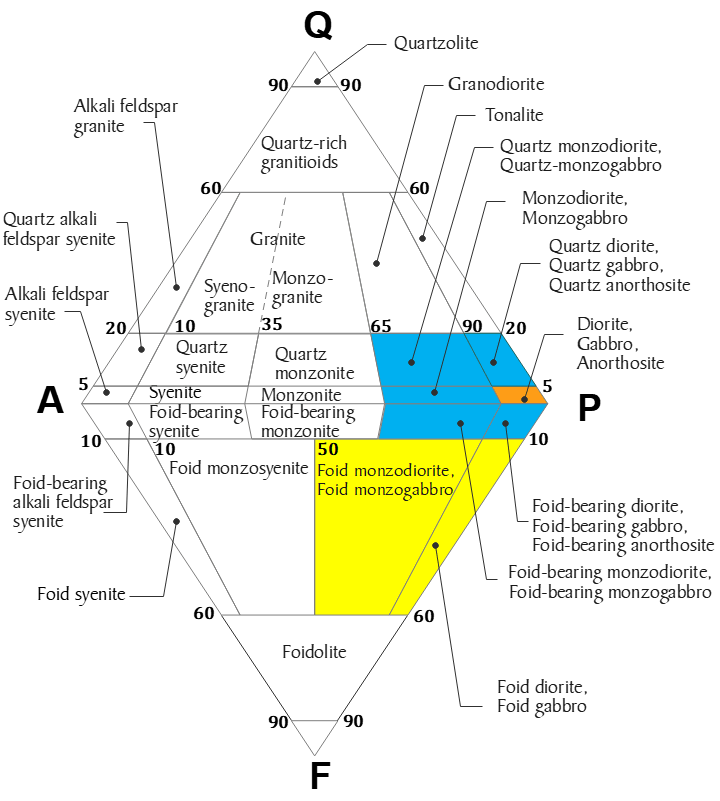

Classification on QAPF

Granite is classified using the QAPF diagram, which is appropriate for intrusive rocks. Gabbro falls into field named (gabbro).

To be classified as gabbro, quartz amount must be below 5%. Alkali feldspar amount must be below 10%.

Plagioclase composition is key. If the anorthite amount is over 50%, the rock is classified as gabbro. If the anorthite amount is below 50%, it transitions into diorite or monzogabbro depending on K-feldspar content.

Lastly, gabbroic rocks is a “catch-all” term for any intrusive igneous rock that is dominated by calcium-rich plagioclase and pyroxene. Gabbro is a specific type. A rock is formally classified as a gabbroid if it meets these three criteria on the QAPF diagram:

- Quartz: Less than 20% (usually less than 5%).

- Feldspathoids: Less than 10%.

- Plagioclase: Makes up more than 65% of the total feldspar content.

Gabbroic rocks types and varieties

- Norite: Contains mostly orthopyroxene rather than clinopyroxene. Common in continental layered intrusions. Example: Bushveld.

- Olivine gabbro: Olivine amount typically 5%–25%. Forms from primitive mantle melts.

- Troctolite: Mostly plagioclase + olivine, pyroxene <5%. Example: oceanic cumulates.

- Monzogabbro: Plagioclase amount >65%, alkali feldspar 5%–10%, quartz <5%. Transitional rock.

- Gabbronorite: Mix of ortho- and clinopyroxene. Example: deep ocean crust.

- Anorthosite: Plagioclase amount >90%, pyroxene + olivine very low. Example: Adirondacks, Moon.

- Essexite: Alkaline gabbroic rock with nepheline. Rare continental alkaline variety.

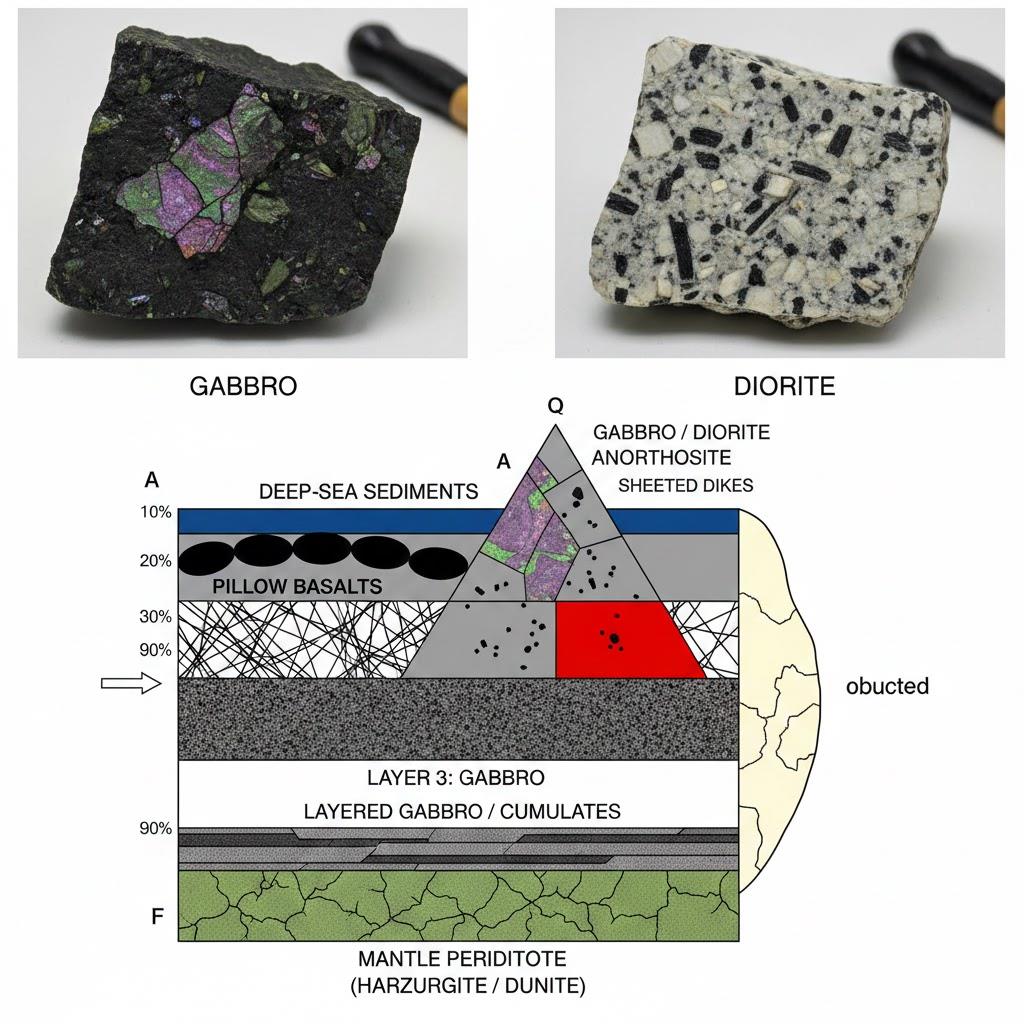

Formation of gabbro and tectonic settings

Gabbro forms from slow crystallization of mafic magma deep in the crust, allowing large crystals of plagioclase, pyroxene, and olivine to grow. Mafic magma is typically produced by partial mantle melting.

Fractional crystallization in large magma chambers can also form the layered gabbro intrusions. Dense early-forming minerals (olivine, pyroxene, plagioclase) settle, creating cumulate layers. Examples: Bushveld (South Africa) and Stillwater (USA) complexes, with rhythmic gabbro and chromitite layers.

Common settings where these rocks form include mid-ocean ridges, back-arc basins, and continental rifts:

- Mid-ocean ridges: Magma rises from decompression melting, stalls in crustal chambers, and cools slowly to form the lower oceanic crust (layer 3).

- Back-arc basins: Extension behind subduction zones triggers mantle upwelling and flux melting. Magma may erupts as basalt or cools at depth into gabbro, forming new oceanic crust.

- Continental rifts: Lithospheric thinning induces mantle upwelling and decompression melting, generating mafic magma that intrudes or erupts as basalt floods. Mafic magma that intrudes and stalls at great depths will cool slowly to form massive gabbro and anorthosite bodies. Example: Midcontinent Rift, USA (Duluth Complex).

How gabbro occurs and tectonic settings

Gabbro rarely occurs as small dikes or thin sills because its coarse-grained texture requires the slow cooling found in large, deep-seated magma bodies. It primarily forms through the following modes:

- Lower Oceanic Crust: A continuous 4–5 km thick layer (Layer 3) that forms the foundation of all ocean basins. Example: The Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

- Layered Mafic Intrusions (LMIs): Massive, basin-scale bodies where minerals settle into distinct “rhythmic” layers. Example: The Bushveld Complex, South Africa.

- Ophiolite Complexes: Portions of the ancient seafloor and upper mantle thrust (obducted) onto land, exposing the gabbroic layer. Example: The Semail Ophiolite, Oman.

- Massive Plutons: Large, relatively uniform intrusions that lack the rhythmic layering of LMIs. Example: The Cuillin Hills on the Isle of Skye.

- Rift-Related Intrusions: Thick complexes formed during continental breakup where magma pools in the thinning crust. Example: The Duluth Complex (Midcontinent Rift), USA.

Where is gabbro found?

- Africa: Bushveld Complex, South Africa that hosts Ni-Cu-PGE ores.

- North America: Duluth Complex (Minnesota), Stillwater Complex (Montana), Adirondacks (NY).

- Europe: Skaergaard (Greenland), Cuillin Hills (Scotland) with strong coastal erosion exposure.

- Asia: Kohistan Arc (Pakistan), Troodos Ophiolite (Cyprus).

- South America: Guiana Shield intrusions, Brazil mafic complexes.

- Australia: Giles Complex characterized by a deep crustal mafic intrusion.

- Antarctica: Dufek Massif, a layered mafic complex with magnetite seams.

Uses and significance

Gabbro is a high-value industrial rock. It supports infrastructure, manufacturing, and geoscience research.

- Dimension stone: Sold commercially as “Black Granite.” Used for countertops, tiles, and monuments due to polish quality and abrasion resistance.

- Highway aggregate: Used as crushed stone base. Its strength commonly exceeds 200 MPa, making it more resistant to crushing than limestone or many granites.

- Rail ballast: Supports railroads due to low porosity and high load-bearing capacity, reducing breakage under vibration stress.

- Concrete and asphalt: Used as durable aggregate. Its density improves concrete mass stability for heavy construction.

- Ni-Cu-PGE ore host: Forms magmatic sulfide deposits. Supplies critical metals for batteries, electronics, and catalytic converters.

- Chromite and oxide layers: Some layered gabbros contain chromite or magnetite seams. These support steel and industrial mineral extraction.

- CO₂ mineralization potential: Mafic intrusions like gabbro can store carbon through mineral carbonation, forming stable carbonate minerals.

- Geothermal research: Used to study deep crustal heat transfer and hydrothermal fluid circulation in rift and oceanic systems.

- Seafloor spreading studies: Lower ocean crust gabbro preserves crystal records of magma chamber cooling, helping reconstruct crustal accretion rates.

- Planetary geology analog: Used to interpret mafic crust formation on the Moon and Mars, especially for anorthosite-gabbro associations.

Sometimes. While gabbro itself isn’t a magnet, it often contains significant amounts of magnetite or ilmenite (iron-titanium oxides). If these minerals are present in high enough concentrations, a hand-held magnet will stick to the rock. Large underground gabbro formations can even cause “magnetic anomalies” that interfere with compasses.

To the naked eye, they look very similar, but geologists tell them apart by their appearance and mineral chemistry. Gabbro contains “calcic” plagioclase (rich in calcium). It is usually darker (black/dark green). On the other hand, diorite contains “sodic” plagioclase (rich in sodium). It often has a “salt and pepper” look because it contains more light-colored minerals than gabbro

In the world of outdoor sports, gabbro is famous for its “friction.” Because the crystals are large and weather at different rates, the surface of the rock stays very rough and “grippy,” even when wet. This makes it a favorite for climbers in places like the Isle of Skye in Scotland.

Gabbro and basalt are made of the same minerals, with the main difference where they cooled and resulting textures. Basalt is extrusive; it cools quickly on the surface (from lava), resulting in tiny crystals.

Gabbro, on the other hand, is intrusive; it cools slowly underground, resulting in large, coarse crystals.

References

- Le Maitre, R.W. (2002). Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms. Cambridge University Press.

- Winter, J.D. (2010). Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Pearson.

- Philpotts, A.R., Ague, J.J. (2009). Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Cambridge University Press.

- Charlier, B., Namur, O., Grove, T. (2015). Layered Intrusions. Springer.

- Rollinson, H. (2007). Early Earth Systems. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wilson, M. (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Springer.

- McBirney, A. (2007). Igneous Petrology. Jones & Bartlett.

- Gill, R. (2010). Igneous Rocks and Processes. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bédard, J. (2018). “Petrogenesis of Lower Oceanic Crust Gabbros.” Earth-Science Reviews, Elsevier.

- Naldrett, A.J. (2004). Magmatic Sulfide Deposits. Springer.