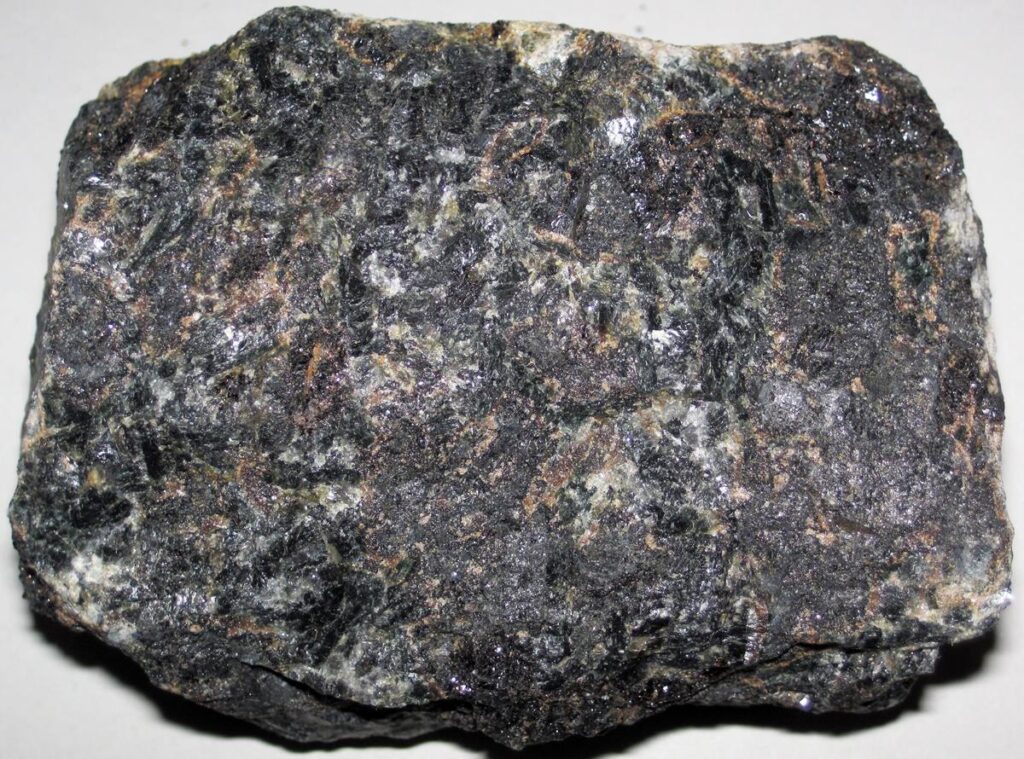

Norite is a mafic, coarse-grained, plutonic igneous rock composed predominantly of orthopyroxene and calcic plagioclase feldspar. It forms deep in the continental crust from slow-cooling tholeiitic or sub-alkaline basaltic magma, often within layered intrusions or large impact melt sheets.

Classification

- Igneous type: Plutonic (intrusive)

- Magma series: Sub-alkaline to tholeiitic

- Silica saturation: Low quartz (<5%)

- Mineral class: Orthopyroxene gabbro (IUGS equivalent)

- Tectonic Setting: Layered intrusions, lower crust, impact structures, continental rift zones

Norite rock physical & mechanical characteristics

| Property | Value / Description |

| Color | Gray, black, or “salt-and-pepper” speckled |

| Grain size | Coarse (phaneritic), 1–10+ mm, pegmatitic zones 1–5+ cm |

| Hardness | 6–7 (Mohs) due to pyroxene dominance |

| Density | 2.8–3.2 g/cm³ (heavier than granite) |

| Magnetic behavior | Weak to moderate if magnetite/ilmenite present |

| Durability | Very high (tough, abrasion-resistant) |

| Strength | Excellent compressive and impact strength |

Chemical Composition

| Oxide | wt.% Range |

| SiO₂ | 42–52% |

| MgO | 8–18% |

| FeO + Fe₂O₃ | 10–20% |

| CaO | 6–12% |

| Al₂O₃ | 12–18% |

| Na₂O + K₂O | 1–4% (low alkalis) |

| TiO₂ | 0.5–3% |

These chemical composition values explains:

- High density

- Pyroxene + calcic plagioclase mineralogy

- Low quartz

- Common presence of Fe-Ti oxides in ore-bearing noritic layers

Mineral composition

A typical phaneritic norite is composed predominantly of plagioclase, which makes up 50–70% of the rock in the form of 1–5 mm laths. Orthopyroxene constitutes 20–40% with grain sizes of 2–5 mm, while augite is present in amounts less than 10%.

Fe-Ti oxides account for 1–5% of the composition, and amphibole or biotite occurs in trace amounts up to 5%.

The essential minerals of norite are plagioclase and pyroxenes, which define its texture and overall composition, while Fe-Ti oxides and hydrous silicates act as accessory phases, contributing minor but important features such as color, opacity, and late-stage crystallization effects.

In some varieties, such as olivine norite, forsteritic olivine may also be present as an additional essential mineral.

Norite textures

Norite is predominantly a phaneritic rock, but it can have other textures. Let us dive deeper into these textures:

1. Typical phaneritic norite

A typical phaneritic norite is composed predominantly of plagioclase, which makes up 50–70% of the rock in the form of 1–5 mm laths.

Orthopyroxene constitutes 20–40% with grain sizes of 2–5 mm, while augite is present in amounts less than 10%. Fe-Ti oxides account for 1–5% of the composition, and amphibole or biotite occurs in trace amounts up to 5%.

2. Porphyritic Norite

Porphyritic norite forms through two-stage cooling in mafic magmas. Slow crystallization at depth produces large phenocrysts of orthopyroxene (hypersthene or enstatite) and calcic plagioclase (labradorite–bytownite). These early-formed crystals record the deep thermal history of the magma.

As magma rises or spreads into shallower regions, faster cooling creates a fine-grained groundmass around the phenocrysts. This matrix includes microlitic plagioclase, fine orthopyroxene, minor augite, and oxides like magnetite or ilmenite. Occasionally, late-stage hydrous minerals such as hornblende or biotite fill interstitial spaces.

Porphyritic norite is mafic, sub-alkaline/tholeiitic, with phenocrysts often showing magnesium-rich cores and iron-enriched rims. Its bimodal texture preserves evidence of fractional crystallization, helping geologists reconstruct magma chamber evolution and cooling history in deep crustal intrusions.

In thin section, porphyritic norite displays dark blocky orthopyroxene crystals embedded in a gray “salt-and-pepper” matrix of tiny plagioclase laths and fine pyroxene. Opaque oxide minerals appear as small specks, while hydrous minerals occupy late interstitial spaces, not phenocrysts.

3. Ophitic norite

Ophitic norite is defined by plagioclase laths enclosed within larger pyroxene crystals. The larger host crystals, called oikocrysts, are usually orthopyroxene or augite, while the smaller enclosed crystals, called chadacrysts, are plagioclase.

This textural relationship makes the plagioclase appear to “float” inside the pyroxene. Importantly, if orthopyroxene dominates, the rock is classified as ophitic norite, not ophitic gabbro. This distinction is key in identifying the rock’s mineral composition and cooling history.

4. Pegmatitic norite

Pegmatitic norite forms in late-stage, volatile-rich melt pockets, where slow cooling allows very large crystals to grow—often 1–5 cm or more.

The mineral assemblage includes plagioclase, orthopyroxene, hornblende or biotite, and magnetite or ilmenite. These large crystals are usually found in small pods or veins within the noritic intrusion.

Pegmatitic norite is not only visually striking but also provides insight into late-stage magmatic differentiation and the behavior of volatile-rich melts in layered intrusions.

Common varieties

Norite is a versatile mafic igneous rock that occurs in several varieties, each distinguished by its mineral composition, formation conditions, and geological importance. Understanding these types is crucial for both academic research and economic geology.

Olivine Norite: Contains olivine, orthopyroxene (Opx), and plagioclase. This variety is commonly linked to nickel sulfide mineralization and is often found in layered intrusions, making it a target for mining.

Garnet Norite: In this type, garnet replaces pyroxene under high-pressure conditions, typically in lower crust or deep arc roots. Garnet norite forms through metamorphic re-equilibration, offering insights into deep crustal processes and high-pressure magmatism.

Magnetite/Ilmenite-Rich Norite: Characterized by high concentrations of Fe–Ti oxides, this variety is economically important as a source of titanium, vanadium, and iron ores, often forming ore-bearing cumulates in layered intrusions.

Lunar Norite: Composed of plagioclase, orthopyroxene, and low-Ca pyroxene, lunar norite is found in lunar crustal samples. Its presence shows that norite is not exclusive to Earth and plays a role in understanding planetary crust formation.

Formation

Norite forms when magma rich in magnesium and iron cools slowly beneath Earth’s surface, allowing large, visible crystals to develop. It crystallizes within the lower continental crust or upper mantle, typically in layered mafic–ultramafic intrusions or deep plutonic bodies. The dominant minerals are orthopyroxene and calcic plagioclase, which define its composition and dark speckled appearance.

The formation process begins as basaltic or gabbroic magma rises and becomes trapped in deep chambers. As cooling progresses, minerals crystallize in sequence, often producing layered zones where pyroxene and plagioclase settle or grow along chamber walls. Because the melt cools gradually and remains insulated, crystals coarsen, giving norite its phaneritic (coarse-grained) texture. This slow cooling also supports chemical differentiation, helping orthopyroxene become the primary pyroxene rather than clinopyroxene.

Norite is also found in impact and extraterrestrial settings, including the Moon, where magma crystallized in the ancient lunar crust, and in meteorites linked to differentiated parent bodies. On Earth, it commonly associates with economically important intrusions that form during tectonic or mantle melting events, such as continental rifting or plume activity. Its deep origin, slow crystallization, and orthopyroxene dominance distinguish it from similar gabbroic rocks.

Where is norite found?

Norite occurs in layered intrusions, impact melt sheets, and ancient continental crust, highlighting its geological and economic importance.

- Bushveld Complex (South Africa): One of the largest norite-rich intrusions, hosting platinum group elements (PGE), chromium, and vanadium ores. A prime site for studying magmatic differentiation.

- Stillwater Complex (USA): A classic noritic cumulate site for understanding mantle-crust processes and PGE mineralization.

- Sudbury Igneous Complex (Canada): An impact-generated noritic melt sheet rich in Ni-Cu-PGE ores, offering insights into impact magmatism and ore formation.

- Great Dyke (Zimbabwe): A linear norite intrusion interlayered with pyroxenite, key for platinum, chromium, and nickel deposits and layered intrusion studies.

- Archean Crustal Belts (Greenland, etc.): Ancient norite occurrences show their role in early continental growth and crustal differentiation.

Norite uses

- Construction aggregate: Norite’s high toughness and durability make it ideal for road construction, concrete production, and rail ballast, providing long-lasting structural support in heavy-use infrastructure.

- Dimension or decorative Stone: With its ability to take a high polish, norite is often used in countertops, flooring, and decorative building facades. Commercially, it is sometimes mislabeled as “black granite” due to its dark appearance and polished finish.

- Mining host rock: Norite serves as a significant source rock for Nickel, Copper, Titanium, Vanadium, and Platinum Group Elements (PGEs), making it economically important for mineral exploration and industrial metal extraction.

- Scientific Research: Geologists use norite to study magma chamber differentiation, mantle-crust interactions, and the evolution of igneous rock systems, providing insights into the Earth’s interior processes and layered intrusions.

Refences

- Barrell, J. (1914). The Strength of the Earth’s Crust. Journal of Geology.

- Condie, K. C. (2016). Earth as an Evolving Planetary System. Academic Press.

- Frisch, W., Meschede, M., & Blakey, R. (2011). Plate Tectonics, Continental Drift, and Mountain Building. Springer.

- Klein, C., & Philpotts, A. R. (2017). Earth Materials: Mineralogy and Petrology. Cambridge University Press.

- Grotzinger, J., & Jordan, T. (2014). Understanding Earth. W.H. Freeman.

- Gupta, H. K. (2021). Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics. Springer.

- Scarselli, N., Adam, J., & Chiarella, D. (2020). Regional Geology and Tectonics. Elsevier.

- Blatt, Tracy & Owens, Petrology: Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic (3rd ed., 2006)

- Philpotts & Ague, Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology (2nd ed., 2009).