Aphanitic texture is one of the common igneous rock textures, especially volcanic rocks. It forms almost entirely through the physics and chemistry of crystallization from silicate melt, unlike sedimentary structures or metamorphic fabrics.

This texture, therefore, is one of the most diagnostically useful; it signifies rapid cooling in volcanic or near-surface environments where crystal growth time is severely limited.

The term is derived from the Greek aphanḗs, meaning “unseen” or “imperceptible.” What appears to the unaided eye as a smooth, homogeneous rock is actually a densely intergrown crystalline framework formed in a geologic instant.

Defining aphanitic texture

In petrology, aphanitic texture refers to an igneous rock groundmass dominated by crystals smaller than 0.1 millimeters in diameter (typically 0.01–0.05 mm).

The key diagnostic features:

- Crystal size: Less than 0.1mm in diameter

- Visual Resolution: Mineral boundaries cannot be distinguished without at least a 10× hand lens. Even with a lens, one typically sees “glints” of light rather than distinct geometric grains.

- Crystallinity: Unlike glassy rocks (like obsidian), aphanitic rocks are fully crystalline. They possess a long-range atomic order that glass lacks.

Aphanitic texture under the microscope

To truly see an aphanitic rock, geologists create a thin section. A sliver of rock is ground down to about 0.03 mm thick—so thin that light can pass through it.

Under a petrographic microscope using polarized light, the “solid” gray rock transforms into a kaleidoscope of colors. Wha you expect to see is:

- The matrix: Even under magnification, the background (groundmass) looks like a dense mosaic of tiny interlocking shards.

- Microlites: You may see tiny, needle-like crystals called microlites, often made of plagioclase feldspar.

By observing how these tiny grains extinguish light, geologists can determine if the rock is basalt, andesite, or rhyolite.

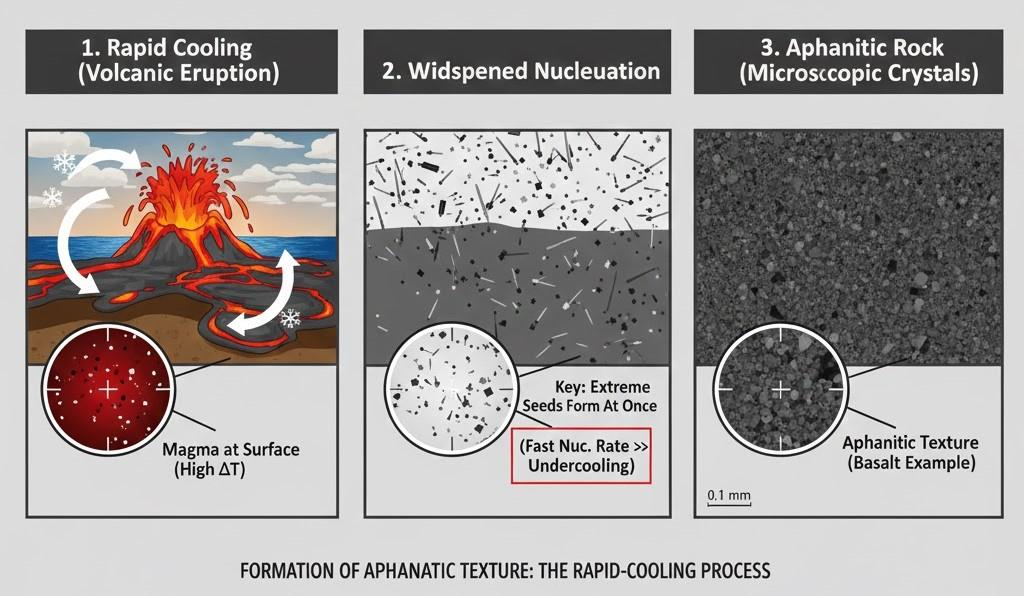

The physics of formation: nucleation vs. growth

The defining control on aphanitic texture is the cooling rate. Crystallization involves two competing thermodynamic processes:

- Nucleation rate: How quickly new “seed” crystals begin forming.

- Growth rate: How quickly do those crystals enlarge once they have nucleated.

In rapidly cooled lavas, the melt becomes highly undercooled (dropping far below its liquidus temperature). This causes a “population boom” or mass nucleation of crystals where nucleation accelerates dramatically, but growth is suppressed.

Because the temperature drops so fast, ions such as Ca²⁺, Na⁺, Fe²⁺, and Mg²⁺ cannot migrate (diffuse) through the melt efficiently to build large lattices. This results in millions of microscopic grains rather than a few large ones.

Experimental petrologist Lofgren (1974) demonstrated that high undercooling causes minerals like plagioclase to form tiny, needle-like “microlites” rather than mature grains.

Lastly, Viscosity also plays a secondary role. High-silica melts such as rhyolite are more polymerized, meaning the melt structure is already resistant to atomic movement. This is why rhyolite almost always forms aphanitic or glass-bearing textures — even modest cooling traps crystals at microscopic sizes because diffusion is physically hindered

Geologic environments that create aphanitic rocks

While primarily associated with volcanic eruptions, aphanitic texture forms anywhere heat can dissipate rapidly into the surroundings.

1. Volcanic surface flows

Basaltic lavas erupt at temperatures up to 1,200°C. When they hit air or water (which are 1,000°C cooler), the thermal shock drives near-instantaneous quenching. Under the microscope, basalt reveals a dense groundmass of calcic plagioclase, clinopyroxene, and Fe-Ti oxides, sometimes accompanied by olivine microphenocrysts.

2. Shallow magma transport (dikes and sills)

Magma injected into narrow cracks in “cold” crustal rock (shallow intrusions) loses heat quickly. Walker (1993) documented that these shallow dikes often develop micro-crystalline textures indistinguishable from surface flows.

3. Subduction Arc Volcanoes

Andesites from stratovolcanoes are frequently aphanitic. Their slightly higher viscosity (thickness) further hinders crystal growth, resulting in a “felted” groundmass of plagioclase microlites.

Thin sections show plagioclase microlites in flow alignment, amphibole microcrysts, and pyroxene in a felted groundmass — a signature of fast cooling but slightly higher viscosity than basalt.

4. Explosive ash and lapilli deposits

While pyroclasts are often associated with glass, the crystalline fragments within fine volcanic ash may still be aphanitic if crystallization began before fragmentation. Cashman (1990) showed that crystal nucleation commonly begins in magma chambers prior to eruption, meaning erupted material can be micro-crystalline even when explosively fragmented.

Essential mineral composition

The mineralogy of these rocks is predictable based on the chemistry of the melt. The most common minerals found in an aphanitic groundmass include:

- Plagioclase feldspar: Often appearing as tiny, needle-like laths.

- Pyroxene: Forms equant, short prismatic microcrysts in basalts.

- Iron-titanium oxides: Magnetite and ilmenite provide the dark, opaque “fill” between other crystals.

- Olivine: May appear as granular microlitic grains in mafic rocks.

- Quartz: Rare in aphanitic rocks because high-silica melts (rhyolite) often turn to glass before quartz can crystallize.

Which igneous rocks exhibit aphanitic texture?

Most aphanitic rocks are classified based on their chemical composition (how much silica they contain). Here are the primary examples:

1. Basalt (mafic)

The most common aphanitic rock on Earth. It is dark green to black and rich in iron and magnesium. Basalt makes up the entirety of the ocean floor and famous landmarks like the Giant’s Causeway.

2. Andesite (intermediate)

Named after the Andes Mountains, this rock is typically gray or medium-dark in color. It is common in volcanic arcs above subduction zones.

3. Rhyolite (felsic)

The volcanic equivalent of granite. It is high in silica and usually light-colored (pink, light gray, or tan). Because rhyolitic lava is very thick (viscous), it almost always forms aphanitic or even glassy textures.

4. Komatiite (ultramafic)

A very rare, ancient volcanic rock. It formed when the Earth’s mantle was much hotter, allowing ultramafic melt to reach the surface and cool quickly into a fine-grained or “spinifex” texture.

5. More examples

More example of rocks with aphanitic texture are dacite, trachyte, phonolite, latite, tephrite, basanite, felsite, and trap rock (engineering term).

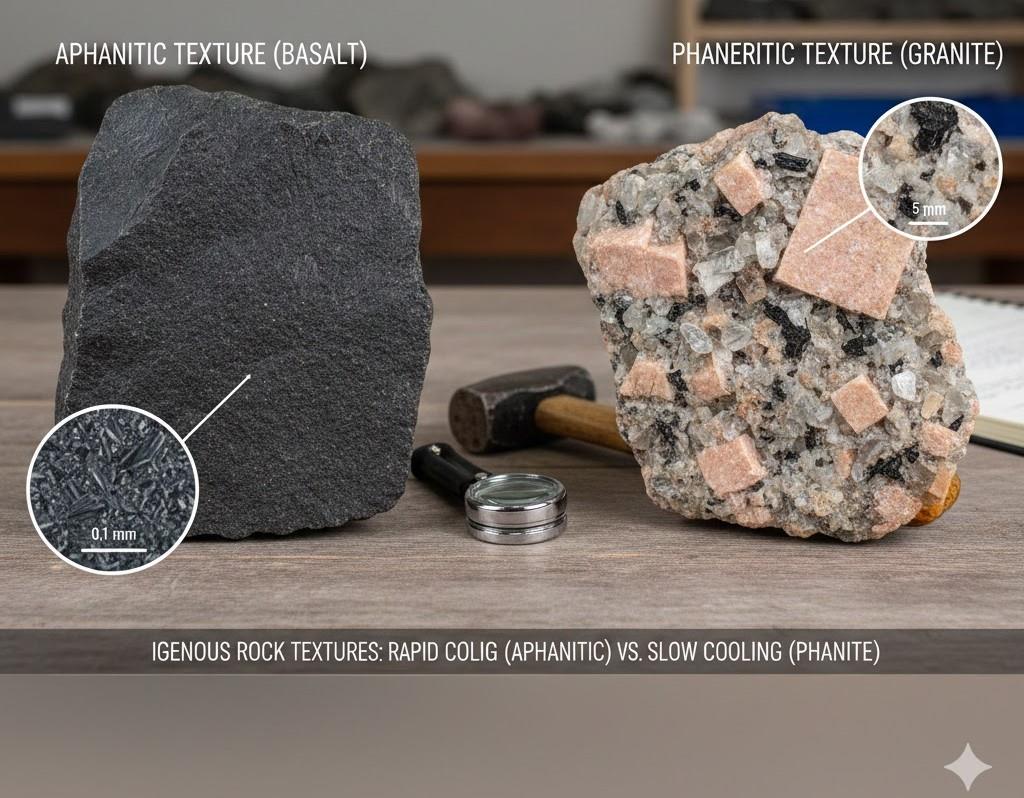

Aphanitic vs. phaneritic

Aphanitic rocks indicate not just fast cooling, but high heat loss relative to melt volume, commonly tied to surface volcanism, small intrusive bodies, or water-assisted quenching.

Phaneritic rocks, by contrast, are formed in thermally insulated plutons where cooling spans tens of thousands to millions of years, permitting large interlocking crystals.

A summary of the differences between aphanitic and phaneritic is:

| Feature | Aphanitic | Phaneritic |

|---|---|---|

| Grain Size | < 0.1 mm (Fine) | > 0.1 mm (Coarse) |

| Cooling | Rapid / Quenched | Slow / Insulated |

| Environment | Extrusive (Lava) | Intrusive (Plutonic) |

| Strength | Higher compressive strength | Variable; larger cleavage planes |

| Crystal growth | Many tiny crystals | Fewer, large crystals |

| Examples | Basalt, andesite, komatiite and rhyolite | Gabbro, diorite, peridotite and granite |

Porphyritic-aphanitic rocks

It is common to see large crystals (phenocrysts) floating in an aphanitic background. This “chocolate chip” look tells a two-part story: slow cooling deep underground followed by a sudden eruption that quenched the remaining liquid into a fine-grained mass.

Hammer & Rutherford (2002) reproduced this process experimentally, showing how magma ascent rates and decompression accelerate nucleation, locking in aphanitic groundmass around pre-formed phenocrysts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Usually, no. While a high-quality 10x hand lens might help you see a “sparkle” from crystal faces, the individual boundaries of the grains in a true aphanitic rock require a microscope for clear identification.

Aphanitic rocks are composed of tiny crystals with a structured atomic lattice. Glassy rocks (like obsidian) cooled so fast that the atoms are “frozen” in a disordered state without any crystal structure.

Basalt is the most common aphanitic rock on Earth, making up the majority of the oceanic crust and many volcanic islands like Hawaii.

Generally, aphanitic rocks like basalt are extremely tough and dense because their tiny crystals are tightly interlocked. This makes them excellent for use in construction and as road “metal” (crushed stone).

References

- Lofgren, G. (1974). An experimental study of plagioclase crystal morphology. American Journal of Science.

- Kirkpatrick, R. J. (1981). Kinetics of crystallization of igneous rocks. Reviews in Mineralogy.

- Cashman, K. V. (1990). Textural constraints on the kinetics of crystallization. Geological Society of America.

- Walker, G. P. L. (1993). Igneous dikes and cooling rates. Journal of Volcanology.

- Tarbuck, E. J., & Lutgens, F. K. (2016). Earth: An Introduction to Physical Geology. Pearson.

- Philpotts, A. R., & Ague, J. J. (2009). Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Cambridge University Press.

- USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). Volcanic and igneous rock texture glossary.

- British Geological Survey (BGS): Igneous Rocks Classification