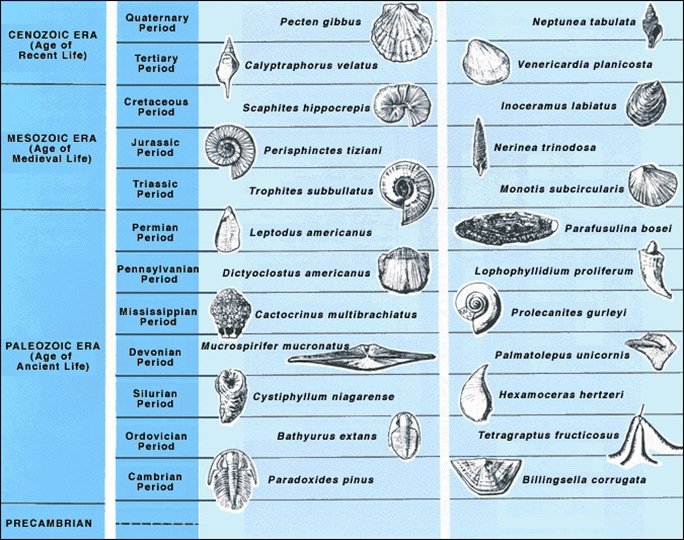

Key, guide, indicator, or index fossils are remains of ancient organisms that were abundant, distinctive, easily recognizable, geographically widespread, and fast evolving, preserved in rock layers. These organisms were also highly preservable within rock strata.

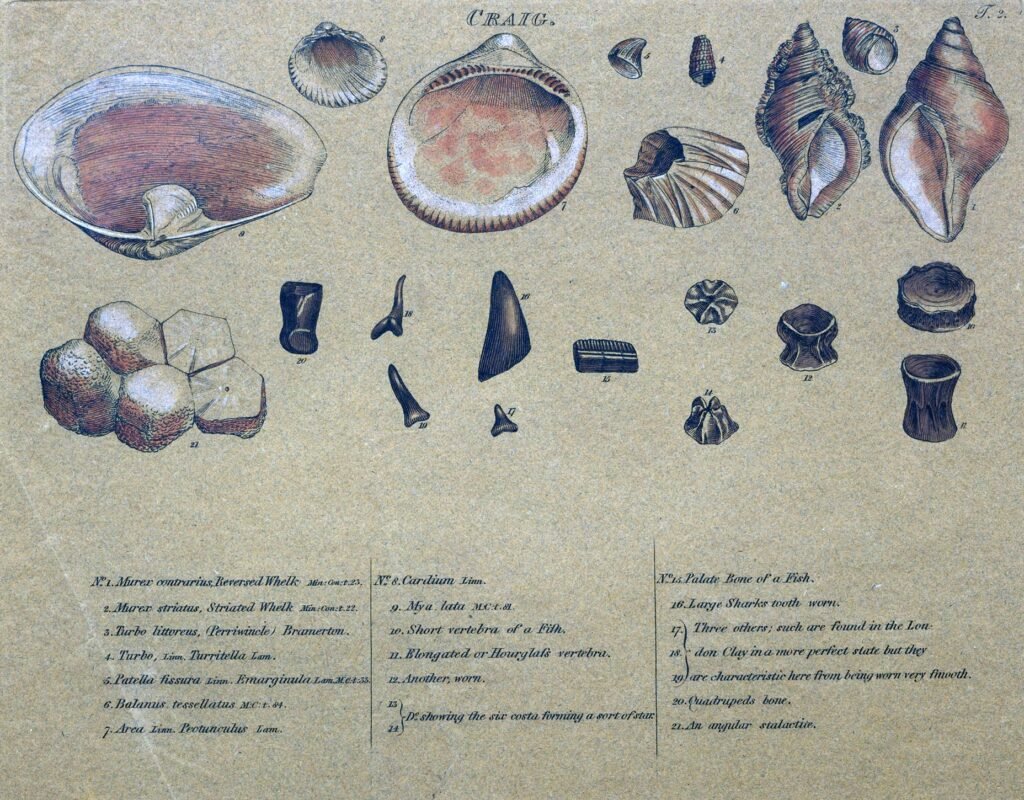

Fossils are remains of past, now extinct organisms – animals and plants -or trails preserved in sedimentary rock strata. They include bones, shells, burrows, feathers, impressions and droppings, or other trails that prove certain fauna and flora existed.

In terms of their size, index fossils can be macrofossils, which are visible without a microscope, or microfossils that need a microscope to see them.

Lastly, geologists and other scientists use index fossils to identify and define geologic periods or faunal stages. These ancient organism remains also help in assigning relative ages and correlating rock layers over a wide area.

Index fossils examples

Trilobites, branchiopods, ammonites, echinoderms, bivalves, corals, diatoms. conodonts, gastropods, foraminifera, and belemnites are some of the common examples. Each of these types has several examples.

Characteristics of index fossils

Characteristics of organisms that make good index fossils are those that are abundant, geographically widespread, and quick evolving. These organisms also need to be distinctive, easily recognizable, and highly preservable.

1. Abundant

Index fossils should be abundant to increase the chance of finding them within rock layers.

2. Geographically widespread

Ideal key fossils should occur in a wide geological area and in different environments. Such organisms can thrive in varying ecological conditions. Remains of organisms restricted to certain facies only reveal ancient environments.

Before you conclude that an organism’s fossils were widespread, beware that waves may distribute their remains like shells or bones to places where the organism didn’t exist.

Tectonic activities that happen after fossilization can also falsely imply certain organisms were widespread over a large geographical area when they were not. For instance, Triassic Pacific terranes only evolved in the paleo-Pacific ocean, but later tectonic activities distributed them to Japan and North America.

3. Evolve and go extinct quickly

Another important characteristic of index fossils is that they should evolve quickly or exist for a short geologic time. These organisms should quickly appear, go extinct forever, evolve into a very distinctive form, or have a high evolution rate.

Fast-evolving organisms, or those that go extinct quickly, help divide strata into smaller units, giving precise relative ages, unlike organisms that take hundreds of millions of years or more to evolve into a distinctive organism.

4. Easily identifiable and distinctive

Good index fossils should have morphologies like shells or skeletons that are distinctive and easily identifiable. For instance, the coiled body, suture, and ornaments on ammonites make them distinctive and easy to identify.

5. Highly preservable

Even with all the above characteristics, how well an organism’s remains fossilize is important. Bony or hard-shelled organisms are, for instance, easier to preserve than slugs, jellyfish, worms, or those with soft bodies, which quickly biodegrade.

Some organisms, like birds, have a large range of bones, but they are poorly fossilized as their bones quickly degrade, leaving fragments hard to identify.

Similarly, ocean currents and other organisms can destroy or scatter the bones of existing organisms, leaving incomplete fragments.

In conclusion, good index fossils should be highly preservable, easy to identify, have a boom and bust, and be distributed over a wide geographical area. Such organisms should also evolve fast into new distinctive forms or go extinct quickly.

Which organisms were good index fossils

Pelagic organisms, i.e., those that lived in an open ocean or sea, like conodonts, graptolites, foraminifera, ammonoids, and certain plankton species, made the best index fossils.

These organisms can float and swim in water, or ocean currents can distribute them or their eggs and larvae over large geographical areas. The marine conditions where most sedimentary rocks form also favored their preservation in large numbers.

On the other hand, benthos, littoral, and land (terrestrial) organisms rarely make excellent index or key fossils. Benthos refers to organisms that live at the bottom of seas or oceans. Littoral organisms live near the shores of the seas, oceans, or other water bodies.

Although they are affected by conditions at the bottom of the sea or ocean, a few benthic organisms make good indicator fossils. Similarly, some of the Cenozoic Era terrestrial mammals, like fast-evolving rodents, are also perfect index fossils.

Finally, plants with spores or seeds dispersed by wind could be excellent indicator fossils. However, not many are, as they are harder to preserve in sedimentary rock strata.

What organisms make bad index fossils?

Bad index fossils evolved slowly and were restricted to certain geological regions, climates, or facies. Ginkgo, for example, only occurs in China, and it hasn’t evolved much for the past 270 million years.

Sharks are also not excellent index or key fossils because they evolved slowly, were not abundant, and were not widely distributed. Their fossils are rare, occur only in certain geographic regions, and are about 420 million years old.

Humans or Homo sapiens will likely make excellent index fossils if they go extinct within a short geologic time interval. Their remains are highly preservable, unique, and easily recognizable.

Importance of index fossils

Geologists, paleontologists and other scientists use index fossils in the following ways:

1. Geologic time scale creation

Index fossils define intervals like eras, eons, epochs, periods, or ages and set some boundaries on a geologic time scale (GTS) or column. For instance, the short-lived mass extinctions, like the Permian-Triassic extension, serve as a boundary on the GTS.

2. Correlate strata over wide geographic area

Stratigraphers use index or fossil assemblages to create fossil zones, which they then use to correlate rock strata worldwide over a wide geographic region.

To correlate strata using index fossils, we must assume that rock layers formed when the organisms existed or were alive. These organisms also lived simultaneously everywhere, not at different times in different places.

The use of fossils to correlate strata is known as biostratigraphy. William Smith, an English canal surveyor and geologist, pioneered the use of these ancient remains of organisms that once lived on Earth to correlate strata. To explain his observations, he postulated the principle of faunal succession.

3. Know relative ages

Organisms whose fossils occur in rock layers lived simultaneously as the rock layers formed. We can therefore use the position of fossils in strata to determine the relative ages of rock strata.

You will, however, need information about the faunal succession of the organisms in question and apply the law of superposition.

4. Know about the past events

Studying index fossils and their distribution helps geologists have a glimpse of past events like mass extension, mountain building, plate tectonics, ancient environments, climates, and facies.

Frequently asked questions

Since index fossils occur in sedimentary rock layers, you need a geologic map to help you locate places with these rocks and whose age is known. Pick an area with outcrops, quarries, excavations, cut roads, or railway lines for ease of access. Take your hammer, chisel, hand lens, loupe, and any other tool necessary and go hunting for these ancient remains of organisms.

Your aim is to select an organism that is abundant, short-lived, and geographically widespread. It should also be easily recognizable and identifiable.

Choose an organism that you spot many times in different stratigraphic columns but is only on a short vertical interval. Such an organism must have been abundant, widespread, and lived for a short time or evolved quickly, making it a good index fossil.